|

MILBRY CATHERINE PHILIPS was born on 08 Feb 1833 in

Davidson Co TN. She died on 11 Sep 1863 in Sylvan Hall, Nashville, Davidson Co

TN. She married WILLIAM PERKINS HARDING on 05 May 1853 in Nashville, Davidson Co TN, son

of Thomas Jefferson HARDING and Elizabeth Waller Bosley. He was born on 18 Sep 1822 in Nashville,

Davidson Co TN. He died on 16 Sep 1903 somewhere in south east Tennessee and was buried in Sylvan Hall cemetery in Davidson

County TN with her husband.

|

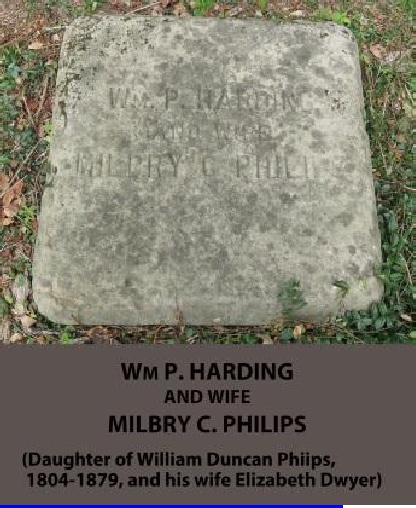

Original Tombstone Sylvan Hall Cemetery

|

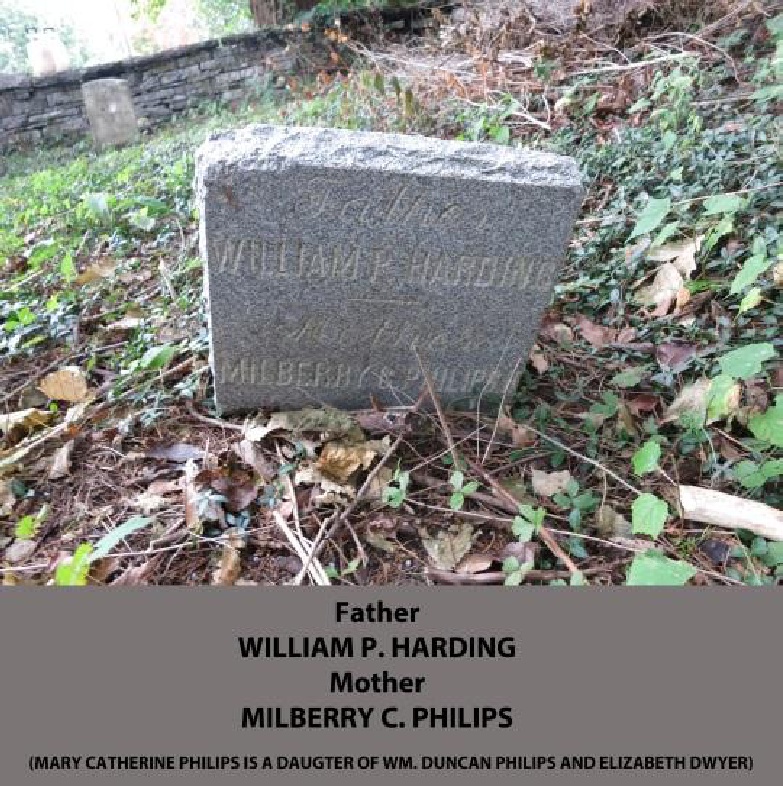

New Tombstone added by family Sylvan Hall Cemetery

|

Milbry Philips and William Perkins Harding had the following children: Madge Bosley Harding - born 2 Feb 1854, died 8 Apr 1936 Mary "Mollie" Demoville Harding - born 18 Oct 1859, died 23 Jun 1942 Married James Hilliard Polk. They had two children. Duncan Philips Harding- born 22 Sep 1860, died 14 Jul 1896 Daniel Dwyer Harding - born 10 Apr 1863, died 16 May 1941

William Duncan Philips' daughter Milberry married William Perkins

Harding on 5 May 1853 and they had a daughter named Mary "Mollie" DeMoville Harding who wrote the following in her memoires:

I was once a little child. Can you believe it? The first time I can remember myself

is when I kissed my mother and hugged her not to cry. She was leaving her home and family the last year of the War of the

States for the South (actually 1863 based on the recorded birth of Daniel and death of Milbrey). Atlanta was to be our destination.

A faithful servant’s illness changed all of our plans.

We had to stop in the little mountain town Clearland, Tennessee where she died after our

mother had tenderly nursed her for some weeks. Our mother contracted typhoid fever, then pneumonia from which she died six

weeks later leaving us a wee baby brother; besides there were three other children of us for our father to care for.

We could not remain in this town after mother had left us, and it was our father’s

desire to take us to our grandmother’s as he had promised (in Nashville, Tennessee). My father faced prison and possibly

death if he returned since all good citizens were given such treatment in those years of turmoil.

After consigning our mother’s body to the grave, my father broken in health

as well as heart broken, packed his little ones into a closed surrey with actual necessities. The mountains over which we

must travel were destitute of food on account of the armies having traveled over them. A thousand dollars a day which my father

offered any good woman who would accompany us to help care for his little ones was no inducement, all saying money would do

them no good for they would never last to enjoy it.

The morning arrived for our departure. The little town turned out to wish us a

safe journey, but in their hearts as friends told us afterwards, they never dreamed we would ever be heard of again.

It was an awful journey, and I scarcely know how to tell you of it. Our older

sister, Madge, ten years old, held the baby. The jogging kept him asleep most of the day, and the nights were spent by my

father walking up and down while the baby cried for the mother to bring him peace. When it was possible we bought milk from

the mountain people. This was warmed and given at intervals. At other times hot water was poured over crushed crackers, then

sweetened and the water was given him. These were before the days of condensed milk and baby foods. His bath each morning

was given him in a large pan used to store things during the day.

Often when we were driving along or rather laboring up the mountain side, men

desperate in appearance would dart out of the bushes bent on robbing, and murder if necessary, and would ask, “Where

is your wife, and who is with you?” When told our mother was no more, they would remark, “You are in a pitiable

plight,” and would sometimes help my father carry us to the bend of the road (for the roads were so cut to pieces that

we would have to leave the surrey that the horse might take our belongings a little higher up the trail).

Well, the days passed on, all of us growing more and more weary and worn. At last

we reached Chattanooga where our cousin Mrs. James Warner lived. We spent the night with her; she cared for us all, and my

poor dear father had his first rest for a week. Sleep he could not; and after he reached Nashville the end of his journey,

he had to receive treatment. At first, he was only allowed to sleep ? hour, then he was aroused and given nourishment; and

so it went for days until at last he could sleep all night, but he was never strong again.

When we arrived in Nashville we went immediately to my aunt’s, Mrs. Felix

De Moville’s. In less than ten minutes the house was surrounded by soldiers ready and awaiting orders to carry my father

to prison. It so happened that a Mrs. Reausaw [mistake for Rousseau] was in the house looking it over

for headquarters for her husband, the General [Lovell Harrison Rousseau] who was in command at that time in Nashville. She,

a stranger and the wife an enemy, wept with our relatives over us. She left suddenly and returned with her husband. He looked

at us for a minute and remarked, "War is hell." He dismissed the guard and gave my father freedom as well as passes in and

out of the city which was very unusual.

Nashville was then under occupation by Union (Northern) troops who were fearful of guerrilla or terrorist

attack and were occasionally threatened by raids of the still powerful Tennessee cavalry in which Mollie’s future husband

James was a young officer. So the Northern forces strictly controlled the movements of the city’s population. Without

a pass, anyone trying to move about was apt to be shot. And suspects, like Mollie’s father, were subject to imprisonment

or at least had their houses surrounded as Mollie recounts. But, at the same time, as she says, the old social ties help so

that individuals, like Mrs. Reausaw, often performed acts of kindness. President Polk’s widow, Sarah Childress Polk,

as the former First Lady, was treated with special consideration by the Union commanders.

|